The psychology of learning times tables

When I became a primary school teacher I had previously spent four years working as an analyst for a large company. I was excited to move to a career that built on my area of interest from my degree – psychology - and hopeful about the impact I hoped I could have on children’s academic and social development. One thing I thought might be a compromise was that teaching young children may not be as intellectually challenging as my work as an analyst had been. Of course I was totally wrong about that. One of the things I love most now about teaching is the intellectual challenge of figuring out the ‘perfect’ way to teach something. And in particular I love working out how to teach mathematical content really well and ways to create really positive attitudes to maths.

So I’ve loved the challenge of working out how to teach times tables so that every child becomes fluent. (For ‘every’ child my view now is that every child accessing a mainstream education in any significant way, and many children who aren’t, are capable of learning times tables to fluency). And what I feel now is that learning times tables is first and foremost a psychological endeavour – for both the children and the teacher.

The psychology for the teacher

When I became interested in times tables teaching, an early realisation was that I was completely unable to explain how a child would learn their times tables. My general approach was as follows:

- An introductory lesson, looking at patterns (e.g. everything in the 6 times table is even, why?), skip counting (Jill Mansergh’s counting stick approach made a regular appearance and I still think it is a brilliant tool), and working out how to derive it from related facts (e.g. if you can’t remember 7 x 6, just do 7 x 3 and double it).

- Stick a copy of the times table into the children’s homework books and send them home with an instruction to ‘learn them’ over the next two weeks

- Give the children a test, which consisted of me reading out a fact (5 x 6) and giving the children probably about 10 seconds to answer (i.e. plenty of time to skip count up or derive from another fact if they couldn’t recall it)

- Move onto the next times table regardless of how well or badly children had done.

- Alongside this, children did a weekly mental maths challenge where they worked up through stages – so some children were churning away at 2s, 5s and 10s every week (which we were no longer practising in class) while others were speeding ahead to times tables we hadn’t yet taught.

But I never looked at this through the children’s eyes. Take a child who was struggling to learn their times tables. They had one lesson introducing the times table and then they were essentially on their own. As a teacher I was outsourcing the learning to people in theory much less qualified than me – the children and their parents. What did I expect to happen at home during those mystical two weeks they had to learn it? It had never occurred to me to wonder that. And when I did start to wonder, I realised I had absolutely no idea. What was the process that would mean that Jacob would know “7 x 6 is 42” just as well as Layla did? I was clueless.

Teachers being able to explain the exact mental process by which every child becomes fluent is at the centre of our Times Tables Fluency programme, and here are the key psychological elements of that:

Memorised as a verbal sound pattern: In our programme children learn to recall each fact as a verbal sound pattern, a bit like learning a song lyric: “Seven sixes are forty-two.” We work towards that sound pattern becoming so familiar that when a child starts reading a fact “Seven sixes are…” then the second part “….forty-two” just trips of their tongue. Watching a child have the experience of the answer just ‘coming out’ of their mouth is quite magical and amazing to them. I’ve heard lots of children say “I didn’t know I knew that” with an amazed smile on their faces. It’s a bit like finding yourself signing along to a song on the radio that you might not have heard from 10 years or so, but the words still just falling out of your mouth.

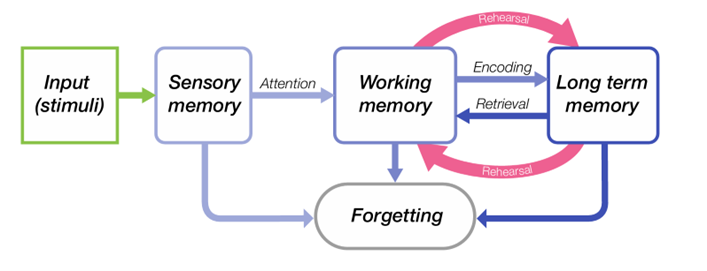

Learnt through a repeated cycle of oral rehearsal and retrieval: For phrases to become stored in long term verbal memory in this way, we need to say them lots of times. The booklets in our programme provide the mechanism for this. Every day the children will try to recall 40 facts (more on this in a second) and then afterwards the teacher will chant every fact, and the children will chant it back. As teacher, you need to prompt the children to chant every fact clearly out loud, which they are all able to do as they are literally just repeating what you say. I’ve noticed that children who mumble are disproportionately likely to start to fall back in scores. A teacher using the programme who has a child with selective mutism has said that her child just chants under her breath and this has worked for her. If I taught a child who didn’t vocalise at all, I would try to teach them to ‘say’ the sound pattern totally silently in their head to try to emulate the chanting. This chanting is the oral rehearsal. Then the second part of the cycle: retrieval. Once the children have had some experience of chanting the facts, you will find that they can also start to retrieve them. Prompt the children to say the start of the fact (“Seven sixes are…”) and see whether something else (hopefully forty-two) comes out. If it does, write it down. If it doesn’t yet, or if they want to check what has come out of their mouth is correct, look up at the display. The display shows all 36 facts, so that if a child doesn’t know a fact yet, they always have somewhere where they can see the correct product. As a maths colleague says “It’s either in here (pointing to her head) or up there (pointing to the display)”. There is no shame in using the display – quite the opposite. It is an essential part of the process of become fluent. During the chanting part of the session they will say the fact lots more times, and in the final targeted support part of the session as teacher you will prompt one or two children, who you have noticed are using the display a little more than peers, to say a target fact several more times to themselves. The following day can you remind them at the start of the session that they have said “Seven sixes are forty two” lots of times now, so may not need to copy today.

In our training we refer to this diagram from the EEF report Cognitive Science Approaches in the Classroom, which shows this cycle of repeated rehearsal and retrieval:

Only having a small number of new facts at a time: The booklets are carefully built up so that children are generally learning around three new facts at time, and everyone is learning those same new facts. More than this and I’ve found that the method of oral rehearsal and retrieval is less effective. This allows you to do little extra bits of practice through the day which are relevant to all children. “As I send each of you out to break I want you all to say ‘seven sixes are forty-two’ to me.”

Intensive practice of new facts, interleaved with ongoing practice of already known facts: Again, the booklets take care of this for you in their design. But take time as a teacher to understand their construction. There’s a note at the bottom of every page and it is also explained in the start of unit video.

Once you really understand this process, you can start of make decisions for yourself about how to use the programme without having to keep checking back to the website. For example, if you have a new pupil, can they just join in? Well, using the above framework, they would have to know the majority of times tables you have taught already as the booklets depend on only having a small number of not yet known facts. So first you would need to find out which times tables facts they know off by heart by conferencing them one-on-one using our fact cards. If they know only two or three facts, and the rest of your class know twenty, the booklets won’t support them, so in this case you would need to refer to our individual pupil intervention guidance.

The psychology for the children

I’ve also found that what children bring to the process, in psychological terms is critical.

Understanding the mental processes behind the approach: Tell the children how the approach works! That we are learning the words to each fact like song lyrics, that each time they say it out loud they are strengthening the memory, which is why we check through the chanting that everyone is saying it loudly and clearly. Tell the children how to retrieve a fact – say the fact out loud with the larger factor first (under their breath if it’s during the booklet session so they don’t disturb peers), then if an answer comes out write it down. If it doesn’t then copy from the display. Unless it is the first day a new fact is introduced, always try saying it out loud first to give yourself a chance of retrieval and see if the answer does pop out - and sometimes it does! – before reading from the display.

Engineer success for every child: The start of the programme goes really slowly. We start with 5 weeks on doubles of numbers to 10 as a bridge into times tables (our doubles and two times tables introductory videos explain this fully). In Week 1, the children just recall double 2, 3, 4, 5 and 10 – facts which some children will have known since Reception, and which you can quickly gap fill for the very small minority of children who don’t know those by January of Year 3. Double 6, 7, 8, and 9 are introduced, one a week, over the following 4 weeks. It is your job to spot on day one of each week any child who doesn’t know any of those, and provide prompts to make sure they do by the end. Your job is to make sure that every child (and we really do mean every child) is getting 40/40 every day. We provide LOTS of guidance on targeted support. Most happens during the session itself, and because the start is so slow you will only have a very small number who need it, which is what makes it achievable for you.

When the children then start the two times table (initially without division facts), you will find they can quickly all get up to 40/40. For any who don’t straight away, intervene very quickly (again following the guidance on our website) to make sure they do. Children love being successful, and because recalling 40 doubles facts in two minutes is so manageable, you’ll find them loving the routine. We hear this time and again from schools, and often they tell us it is children who have struggled with maths who thrive the most, and I suspect this level of success feels particularly good to them.

Because the vast majority of children will get to 40/40 just through the careful booklet design, and retrieval and rehearsal within the sessions, targeted support for the few who need it feels exciting and rewarding rather than overwhelming.

Use the early success to make the process of learning times tables feel totally achievable to children: Once you’ve got the children being successful and feeling great about this, you start to look ahead to the task at hand. You will repeatedly show children the graphic of the 36 facts they need to learn and where they are so far. It’s shown on the class display and also in the start of unit lesson for each new times table. Once you have learnt the 2 times table, the children know 8 of the 36 facts – over a quarter. And after the second times table we learn, the square times table, children know 15 of the 36 facts – nearly a half of the facts they need to learn. By defining and communicating the domain of knowledge (the 36 facts), showing children how quickly they are progressing through them and repeatedly reminding them how successful they are, children will move through the process without times tables ever becoming the amorphous and unmanageable beast I know they have to many children I have taught in the past.

The shift to seeing the learning of times tables as a psychological endeavour has been transformational for me. I started out wanting to teach times tables as a means to an end – getting children to know the facts so that they could access more challenging maths in the main maths lesson. But I’ve learnt to also actually love the process of learning times tables in its own right. We’ve worked incredibly hard to provide resources and guidance embedded in the programme that will – we hope – mean that you learn to love teaching times tables as well.